London’s loss will be Manchester’s gain as the opera company announces it is to create a base in the thriving cultural centre

Describing the recent journey as turbulent would be an understatement; nonetheless, English National Opera (ENO) finds itself in a situation reminiscent of November 2022. Back then, the government warned ENO that it risked losing its entire funding unless it relocated outside London, possibly to Manchester. This directive was a consequence of the cultural policy under then culture secretary Nadine Dorries, aiming to redistribute arts funding as part of the Conservative government’s levelling-up agenda.

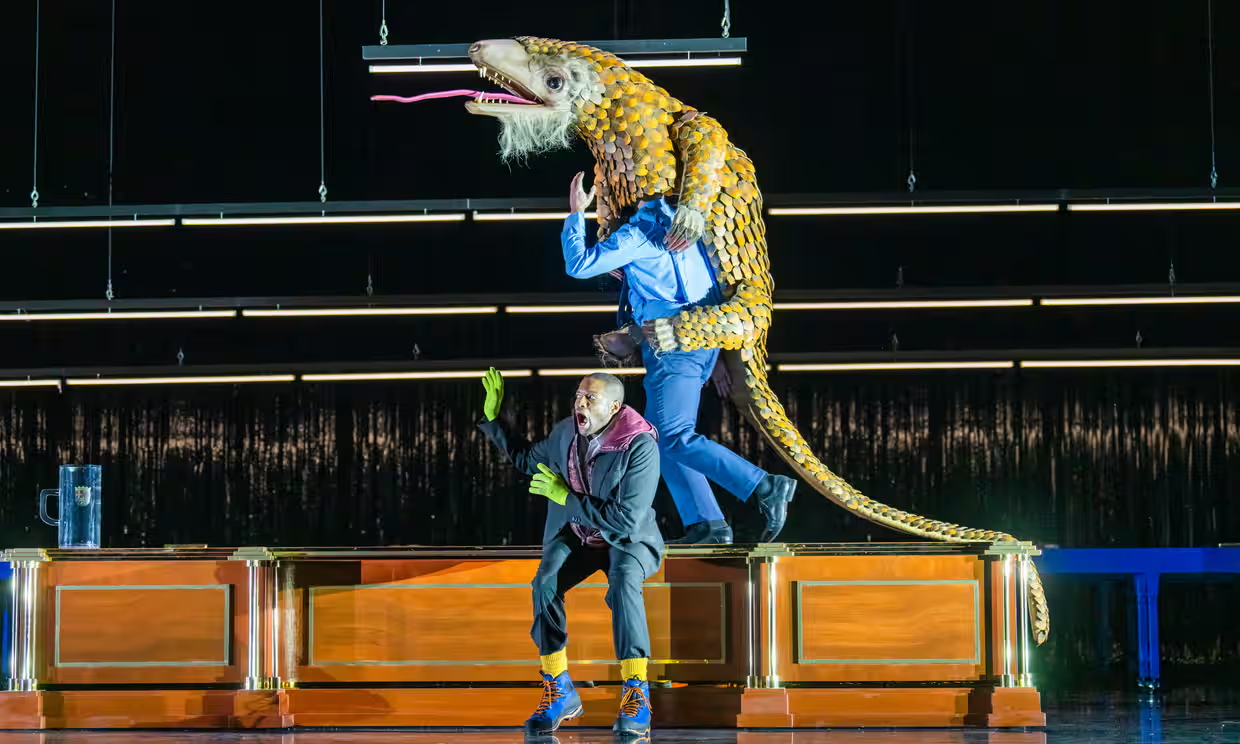

However, the revived ENO will take on a distinct character. While still presenting major productions in its London venue, it will engage in collaborations with various entities in Greater Manchester to create innovative operatic works of varying scales. Notably, ENO has bid farewell to its longtime music director, conductor Martyn Brabbins, who resigned in response to proposals involving job cuts in the orchestra and reductions in the chorus, forming what he termed a “plan of managed decline.”

Is the revised ENO model indicative of a “managed decline”? The suggested workforce reductions and rehiring are integral to a transition towards a brief, five-month season in London. This marks the conclusion of the company’s previous year-round ensemble-focused, large-scale work approach – an approach that offered a more economical, edgier, and accessible alternative to opera audiences in London compared to the Royal Opera House. The shift to a shorter season raises concerns about lost livelihoods and the disruption of a longstanding tradition. A mere five-month season lacks the vitality of a thriving full-time company.

The return to Manchester may seem unexpected. A year earlier, cultural leaders in the city expressed skepticism about having an ENO forced upon them, likening it to cultural missionaries bringing London’s art. Mayor Andy Burnham, in particular, was assertive in stating, “If you can’t come willingly, don’t come at all.”

However, insiders in Manchester suggest a notable shift in the nature of discussions with ENO since Jenny Mollica assumed the role of interim chief executive. The conversations have become more open and collaborative, leading some to rethink their initial reservations and consider the potential for an intriguing collaboration.

From ENO’s perspective, the decision to move centered on discussions with several cities, ultimately narrowing down to Manchester, Liverpool, and Birmingham. Manchester was chosen due to its perceived compatibility with ENO’s vision and its existing cultural landscape. The city boasts a robust infrastructure, including the presence of BBC Radio 3, cultural organizations like Home and Aviva Studios, and renowned orchestras like the Hallé and the BBC Philharmonic.

While some might question whether a city with a less formal cultural offer might have been a better fit, the emphasis is on collaboration and co-production, leveraging Manchester’s established cultural presence.

This move to Manchester brings to mind a historical attempt in 2008 when the Royal Opera House considered establishing a branch in the city. However, this initiative was abandoned due to financial concerns and fears of competing with Opera North’s audience. Presently, Opera North is reportedly open to collaborative efforts to expand opera audiences alongside ENO.

The ultimate assessment of this outcome depends on the quality of the works produced by the reconfigured ENO in partnership with its newfound collaborators in Manchester. In the political game played with the arts, London appears to be the loser, while Manchester emerges as the victor. Whether one approves of this outcome depends largely on one’s geographical standpoint.